Ginger (Zingiber officinale) is well known as a tropical spice. We grow it for its spicy and refreshing taste and its delicious aroma.

Ginger is a “cultigen,” a plant that has never been discovered in the wild. It’s thought to have originated as a natural hybrid somewhere in the region formerly known as the East Indies, now Maritime Southeast Asia: perhaps Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines or New Guinea. And it has been grown in those areas as a spice and medicinal plant for at least 7,000 years, carried from island to island by boat.

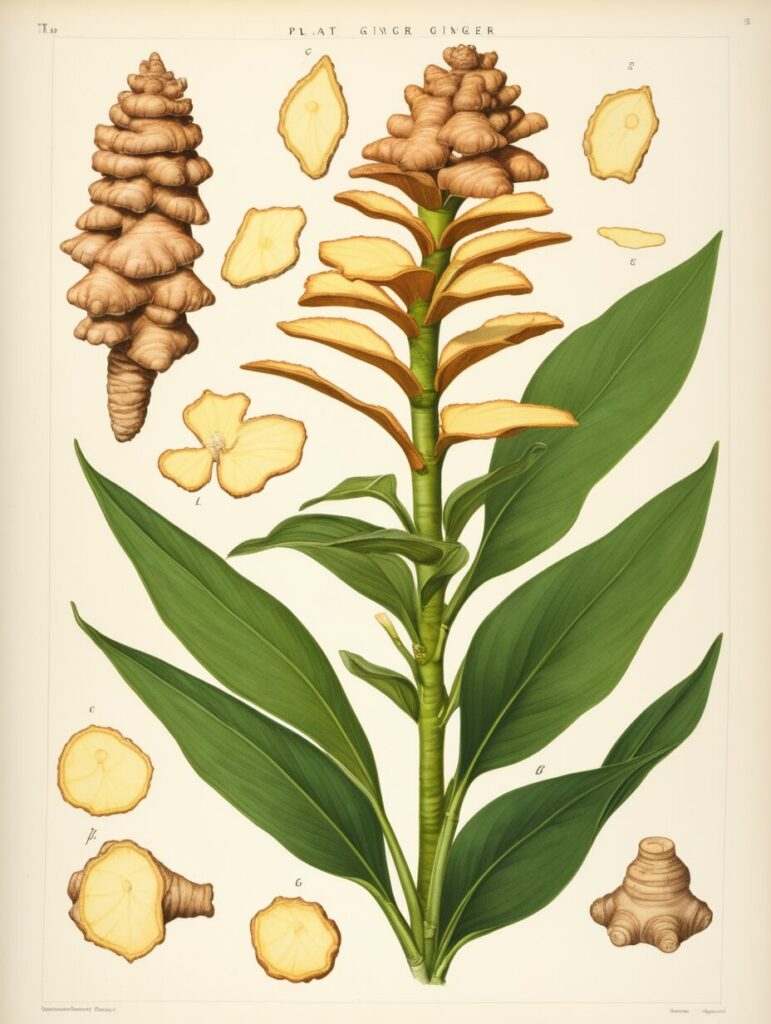

Now ginger is grown in tropical areas all over the world. Ginger as grown in the tropics. Like so many other plants in the Zingiberaceae family, ginger is an understory plant, creeping along the ground under jungle conditions. It produces an annual stem (actually, a pseudostem made up of the rolled bases of its leaves) of narrow lanceolate leaves arising from a thick, spreading, underground or partially underground rhizome.

Flower stalks are borne on separate stems, but are rarely seen. Commons Ginger rarely blooms outside of the hot tropics, so few people have ever seen its conelike inflorescences of purple and yellow flowers that look much like tiny orchids. However, you can grow them in pots in the north. Just bring them inside in the cold times.

Gingers are sterile and produce no seeds. You wouldn’t think you could grow such a tropical plant as ginger in a temperate climate, but in fact you can. It isn’t even that complicated … but you’ll likely need both indoor and outdoor space.

Starting Ginger at Home You don’t grow ginger from seeds, as it produces none, but rather from rhizomes. You may see these called “seed” or “seed rhizomes” in some catalogs, much like tiny potato tubers are called seed potatoes. These rhizomes are harvested from plants grown the previous year. Ginger rhizomes with sprouts starting to show. Look for rhizomes that are starting to sprout, like these.

To grow ginger, you need to find viable rhizomes. However, the rhizomes in your local supermarket have often been irradiated to prevent sprouting. They’ll therefore be useless to you. However, if you see any starting to produce small creamy or greenish growths (these are called eyes) on the rhizome, they’re good to go!

Otherwise, look for organic ginger rhizomes, usually available at health food stores. They haven’t been treated and germinate readily. Prefer a rhizome with several eyes: you’ll get a bigger harvest! Rhizome cut, showing eye. Cut the rhizome into sections, each with an eye.

Start growing ginger indoors in late winter or early spring. Begin by soaking the rhizome in warm water overnight, as this can speed things along a bit. You could plant the entire rhizome as is, but for a greater harvest, cut the rhizome into sections at least ¾ to 1 in (2 to 3 cm) long. Each must have a viable eye.

Fill a 15 cm (6-in) pot about three-quarters full of moist potting soil (plain houseplant potting soil will work well).

Originating from Southeast Asia, this knobby root has traversed centuries, leaving an indelible mark on traditional medicine systems worldwide. One of ginger’s primary medicinal compounds is gingerol, a bioactive substance renowned for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. In traditional Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine, ginger has been treasured for its ability to alleviate various ailments, ranging from digestive issues to respiratory conditions.

The digestive benefits of ginger are particularly noteworthy. It has been employed to ease nausea, motion sickness, and indigestion. Whether consumed as a soothing tea or incorporated into culinary creations, ginger’s ability to calm the stomach has made it a trusted remedy for generations. It stimulates saliva production and digestive enzymes, promoting a smoother digestive process.

Beyond its digestive prowess, ginger emerges as a formidable ally in the realm of inflammation. The gingerol compounds exhibit anti-inflammatory effects, potentially reducing symptoms associated with osteoarthritis and other inflammatory conditions. Its natural analgesic properties may also contribute to alleviating pain and discomfort. Ginger’s influence extends to the cardiovascular system, where it showcases potential benefits. Studies suggest that it may contribute to lowering blood pressure and improving overall heart health. This dual action – calming inflammation and promoting cardiovascular well-being – underscores the holistic nature of ginger’s medicinal impact.

In the domain of respiratory health, ginger has not gone unnoticed. Its anti-inflammatory properties extend to the respiratory system, making it a go-to remedy for managing symptoms of respiratory conditions like asthma. Additionally, its warming nature is believed to help ease congestion and soothe sore throats.

Topically, it has been used to alleviate pain and inflammation in conditions like osteoarthritis and muscle soreness. Ginger compresses and oils are applied to affected areas, providing relief and fostering a sense of well-being. Ginger, with its versatile and profound medicinal attributes, stands as a testament to the intricate relationship between nature and healing, offering a fragrant and flavorful journey to well-being.

COMING SOON, “THE SECRET GARDEN” HERB BOOK, 55 PLANTS THAT GROW ANYWHERE IN THE WORLD AND THEIR GIFTS TO HUMANS.